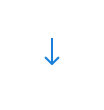

“Beautiful deleveraging” is a phrase coined by Ray Dalio to describe a perfect way out of a debt crisis. What debt crisis? Well…the US. A year ago, we were talking about $32T of public debt. Now, with deficits growing at $2T/a year, or 8% of GDP, we are at $34T, 120% of our Q4 2023 GDP of $28T. How are we getting there? The average rate of interest on public debt is 3.2%. The rest is driven by the factors shown below:

The 3.2% piece is the bar described as Treasury. If we continue to grow the deficit at 8% per annum, it will take 9 years to double , unless we cut entitlements and defense spending…which doesn’t seem likely. Or, unless we grow the economy faster than 8% in nominal terms. If public debt is $68T in 9 years, GDP would need to be $97T in order for the ratio to be a more stable 70%. The implied growth rate is just under 15% to get there. Real GDP growth in 2023 was 2.5%. Inflation in 2023 was 3.4%, so overall nominal GDP growth was 5.9%. So, how do we get nominal GDP to grow faster? More inflation.

Inflation measures have been somewhat manipulated over the years to make things look better than they are. Maybe that is too harsh. The measure of inflation used by the government has been revised over the years to reflect a number of factors, such as quality improvements. So, for example, if the latest model of the iPhone has elements of computing power or processing power greater than the previous version, its price, though greater than the previous model, may be adjusted downward by using something called “hedonics”. Hedonics is related to the Greek word “hedonism”, meaning “of or related to pleasure”. So, if the iPhone has increased in price by $200, but the increase in quality is deemed to be $250, then the iPhone price increase will not factor into a higher inflation measure. The consumer, although they are paying more, is supposed to feel better about the product they are buying and thus not experience the pain of inflation.

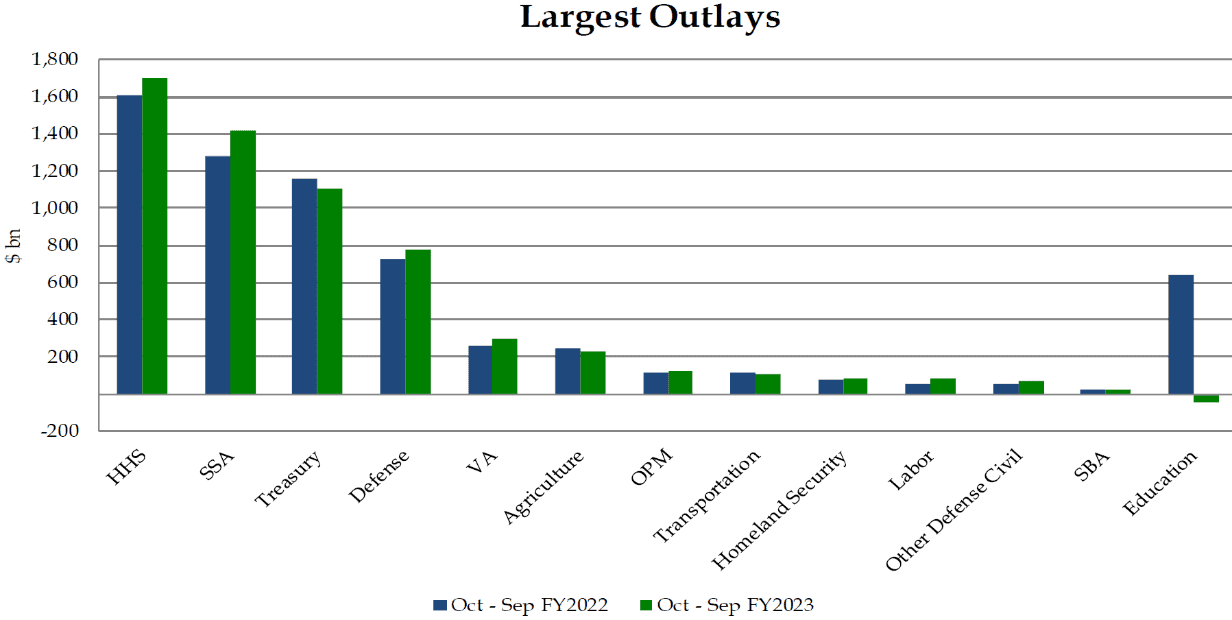

As this practice has developed over the years, it can feel as if the government measures of inflation are disconnected from how people experience inflation in their everyday lives. A recent post from a former Treasury secretary, Larry Summers captures this:

Okun is an economist who worked in the 60s and 70s. Summers is trying to explain why, although inflation is measured as declining, people are not feeling good about it. It is also worth considering the implications of nominal GDP growing at a higher rate than advertised in the context of a so-called beautiful deleveraging and whether the effect of inflation on nominal GDP could work as I suggest. Apparently, it hasn’t been working recently.

There is supposed to be a relationship between inflation and interest rates. If real interest rates, adjusted for inflation, are to be actually increasing the value of investment portfolios after inflation, they should be positive after adjusting for the rate of inflation. So, inflation is 5% and long-term interest rates are 3%, then, in real terms, the value of the investment assets are declining – real rates are said to be negative. This is precisely the effect the US government is looking for because the other side of that equation is that the real value of the debt owed by the government if real rates are negativeis declining.

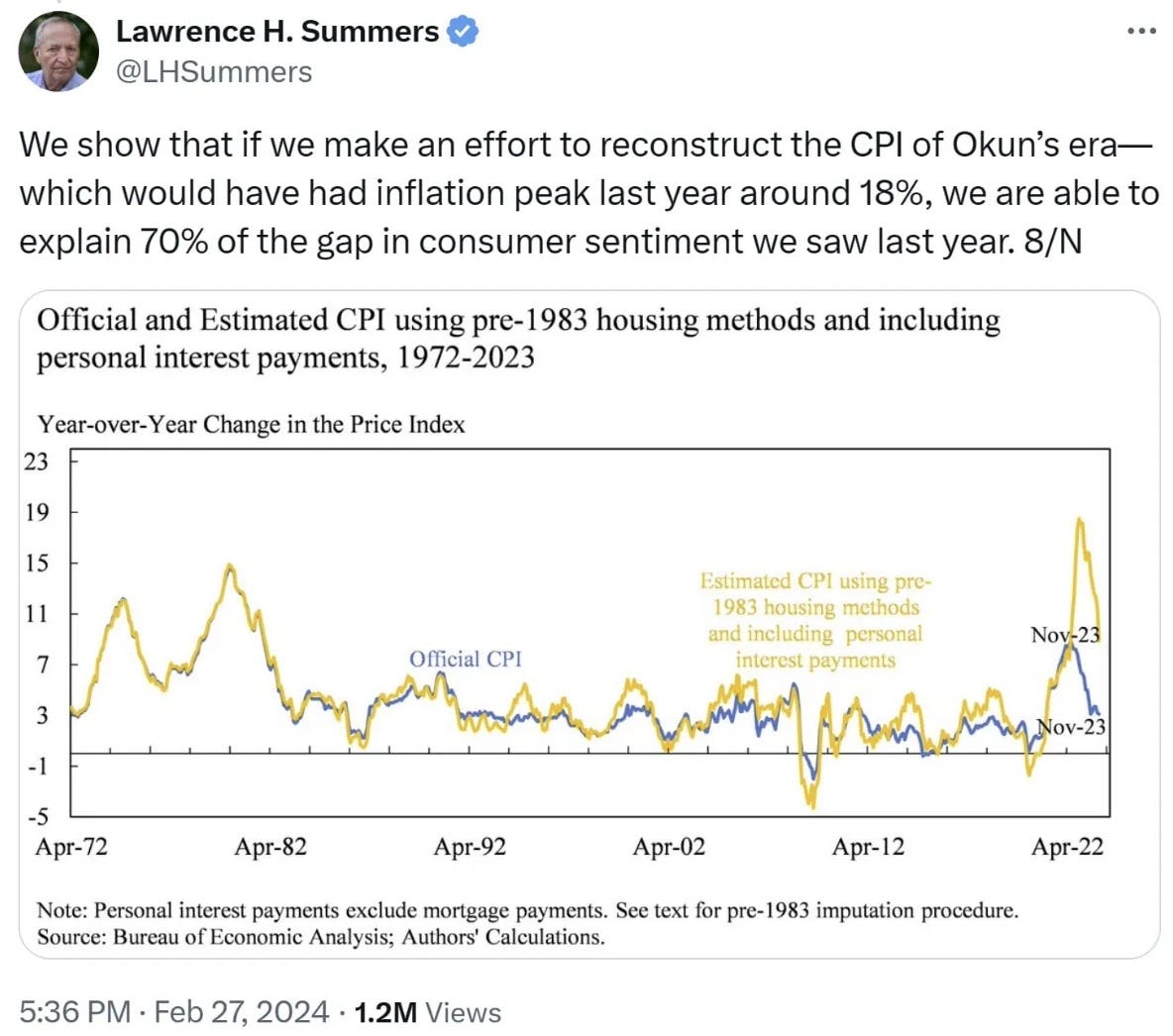

This handy chart produced by Luke Gromen shows what happened in a previous era when nominal GDP was higher than nominal interest rates for a prolonged period:

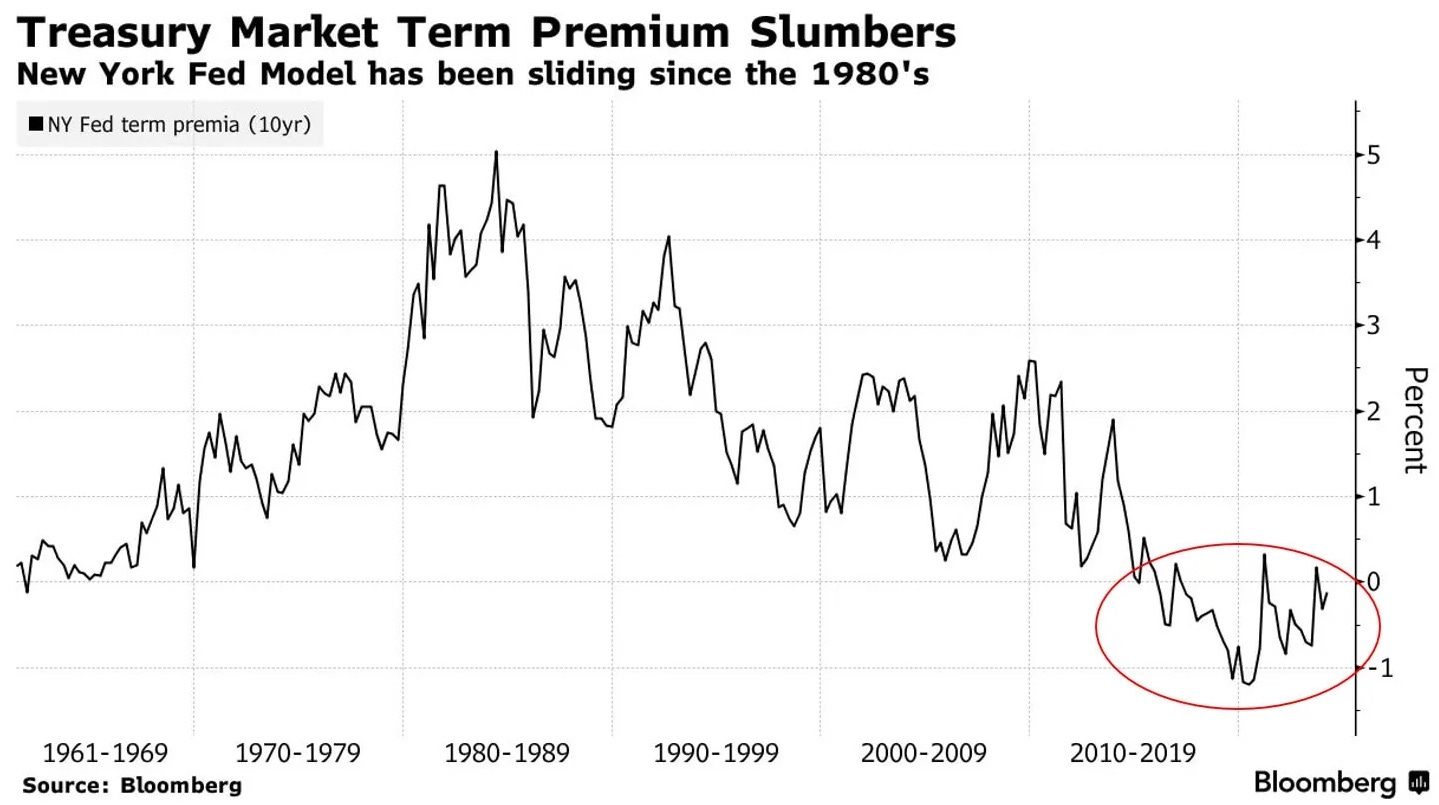

It worked in 1946-1960 when net debt/GDP declined substantially. Not so much for the last 10 years. So, maybe inflation needs to go up? Which would suggest that the market ought to be demanding higher rates of interest for bonds of longer maturity. That isn’t the story told by the yield curve though; nor is that reflected in the so-called term premia.

PIMCO recently published a paper on this phenomenon. Common sense holds that investors should get paid more for taking more risk. This tends to be true in the bond market: the further you extend the maturity of bonds you hold, the more uncertainty you are underwriting and the more you should get compensated. If you own a two-year bond, your principal will be returned after two years (absent default) and you can decide how to reinvest. The problem with a 30-year bond is that after two years, you still have to wait another 28.

Because Treasury issuance at the moment is predominantly at the short end – 80% T-Bills and 20% longer-term Notes vs the more typical 20/80 – it is hard to get a solid read on the market’s view on the longer end of the curve. As I said in an earlier post Liquidity), the10-year Treasury rate may be a little tighter (lower) because of relative scarcity. Mortgage backed securities (MBS) usually trade at a premium (more) than the equivalent maturity 10-year Treasury, but currently are trading at double that.

The beautiful deleveraging the Treasury needs is for inflation to increase GDP in nominal terms without having to increase interest rates to combat inflation. Huh?

What the Treasury really needs is a price indifferent buyer – a buyer not so motivated by considerations of risk, term premia and underlying inflation.

Two candidates are the Federal Reserve through Quantitative Easing or banks incentivized by favorable capital requirements for holding treasuries. The rational investor should not be buying long-term government bonds. There are some clues to whether this is happening.

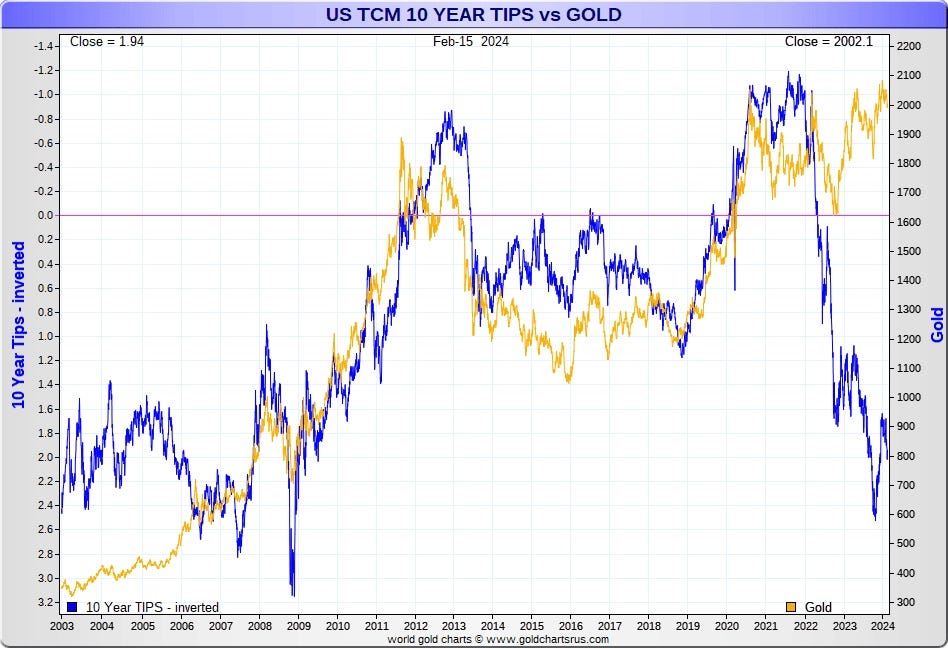

This chart shows something strange: gold price separating from real interest rates. Historically, these two things are negatively correlated, so, when real interest rates rise, the gold price falls. It makes sense because gold has no yield – it’s all about price. Right now, although real rates have been rising, so has gold. That makes sense only if the market is expecting more inflation.

You can wander around in macro land forever, chasing down signals and developing hypotheses. There are lots of stories to explore about gold. For what it’s worth, my thoughts are that we are not done with inflation, at least of the monetary kind. The only way we deleverage is through inflating GDP faster than debt grows and the only way we accomplish that is through more QE of one kind or another. Bonds are not worth owning, gold is, as is bitcoin (though it makes me nervous) and real assets generally. More on gold another day…